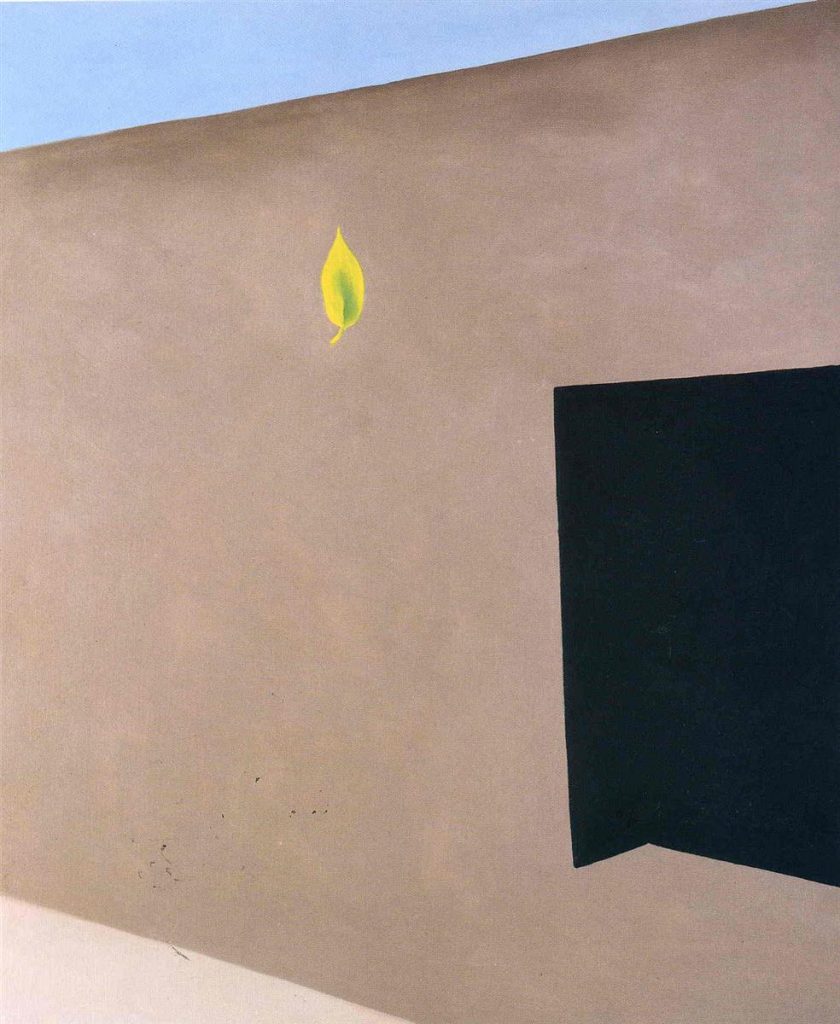

In a recent visit to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, I walked past Georgia O’Keeffe’s morning glories and edificial irises and stood mesmerized by a painting that was far more humble, far less glamorous. A wall with a door in it, an expanse of smooth brown adobe centered by a core of a rough black square of absolute negative space.

O’Keeffe liked to paint the same thing again and again, until she had penetrated it to its essence, unraveling the secret of her attraction. The flowers, the blowsy petunias and jimsonweed, were superseded by New York cityscapes and then by cow skulls and miscellaneous animal bones, surreally aloft over the clean blue skies and dry hills of New Mexico. This was the landscape that unlatched her heart, and it was during her time there in the 1930s that she began to obsess over the wall with a door in it, located in the courtyard of a tumbledown farmstead in Abiquiú, New Mexico. First she bought the house, for $10, a process that took a full decade, and then she set about documenting its enigmatic presence on canvas, creating almost 20 versions. “I’m always trying to paint that door – I never quite get it,” she announced. “It’s a curse the way I feel – I must continually go on with that door…it fascinates me.”

The attraction was a mystery, and yet walls and doors figure large in the story of O’Keeffe’s singular life. How do you make the most of what’s inside you, your talents and desires, when they slam you up against a wall of prejudice, of limiting beliefs about what a woman must be and an artist can do? She didn’t kick the door down – hardly her style – but instead set her considerable canniness and will at finding a new way through.

I see classic patterns, which generate archetypal sacred symbols in O’Keeffe’s work especially the door, the sacred center of her home. Though this dwelling may not be a publicly recognized sacred structure, it serves as the center for O’Keeffe.

Guided by her own intuitive response, almost possessed, O’Keeffe paints this archetypal symbol. The door represents the notion of metamorphosis and transition, a passage from one place to another, between different states, between lightness and darkness. The act of passing over the threshold signifies that one must leave behind materialism and personality to confront inner silence and meditation. It is abandoning the old and embracing the new.

Doors hold the essence of mystery, separating two distinct areas, keeping things apart. There is a barrier, a boundary, which must be negotiated, before the threshold can be crossed. The mysterious beyond is hidden from sight by the closed door, and some sort of action must be taken before the other side becomes visible and available to us. The closed door is full of potential, for anything might lie beyond, as yet unknown and unseen.

At the age of 96, Andy Warhol, another creator of a purely American vernacular, interviewed O’Keeffe. She told him about the landscape that she most cherished, her home and, the wild expanses of New Mexico. “I have lived up there at the end of the world by myself a long time. You walk around with your thing out in the field and nobody cares. It’s nice.”

From the beginning, New Mexico represented salvation, though not in the wooden sense of the hill-dominating crosses she so often painted. O’Keeffe’s salvation was earthy, even pagan, comprised of the cold water pleasure of working unceasingly at what you love, burning anxiety away beneath the desert sun.

Elegance shares a border with crankiness, independence with selfishness, and O’Keeffe was by no means a saint. But without O’Keeffe’s sharp-eyed, sharp-tongued, exacting presence, chaos loomed. She made it happen, that simple door was anything but, and in painting it, she was opening a door to a new kind of American art, a new kind of woman’s life. “Making your unknown known is the most important thing,” she said, “and keeping the unknown always beyond you.”